By Joe Byrne

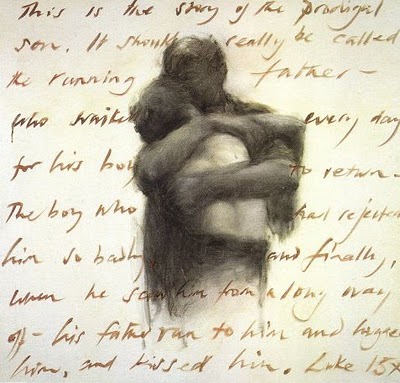

The parable of the prodigal son is perhaps Jesus’s most popular short story. It is used as shorthand for what is best in the Christian religion: generosity, forgiveness, redemption, unconditional love.

I’m not the first person to suggest that in this parable there is more than one prodigal son. Arguably there are two prodigal sons in the parable—and they are prodigal in different ways. I would also suggest there is a prodigal father. And before I’m through I’ll talk about prodigal apostles, churches, nations and gods. Prodigality is my theme. It certainly seems to be the theme that those who chose the lectionary readings want us to consider.

Prodigality is one of the central narratives of Christianity. The Christian path is a wayward path. It is the story of going astray, of taking the wrong path and finding our way back to the right path. In some ways that is the path, and we never find our way to the right path except by wandering off the path first. We find our way in the wilderness, and paradoxically never find the way by hewing to the straight and narrow.

Definitions of Prodigal

- Being wasteful of resources; or extravagant generosity.

- Engaging in, and then repenting, acts of moral depravity.

In Jesus’s story, the prodigal son is thought to be prodigal according to both these definitions. The father—and by extension, God—is prodigal according to the first definition. And on this fifteenth anniversary of 9/11/2001, I would say that the United States has been prodigal according to both definitions. Just as the prodigal son had his metanoia, his repentance, we must hope that the United States might also change its ways and find its way back to the right path. More on that later.

Confessions of a Prodigal Son

Before that, let me say something about my own prodigality. I consider myself a prodigal son. I certainly felt that way when I returned to the Christian path, and particularly to the faith-based peace movement, after eighteen years in the wilderness. In 1996, I left the Catholic Church. I told people that I was leaving the Church to become a Buddhist, but I wasn’t much of a Buddhist during those eighteen years, though I periodically practiced. I didn’t really leave one church to join another; what I was really doing was trying to live a life unencumbered by dogmas and moral rules. While I didn’t live a life of dissolution, like the prodigal son—I didn’t have half an estate to blow!—I did do drugs and engaged in sexual promiscuity. Some might call this moral depravity; I was certainly wasteful of the gifts God had given me. Eventually, I realized that a life dedicated to hedonism, and a life lived in bitter reaction to the more repressive aspects of religion, was not a very satisfying one. So I came back to the Church, to the faith in which I was raised, the faith that had formed my heart and mind and soul, and my sense of mission in the world. I wouldn’t characterize this return as repentance as such, or as a deep conviction of my sinfulness; I was driven, instead, by a desire to be reconciled to my better nature, and to God.

The same is true of my return to the faith-based peace movement, to the Atlantic Life Community (ALC). After eighteen years away, I naturally assumed that everyone assumed I was a government agent, a spy. Who knows, some in the ALC might still think this. If so, at least I’m a spy with a good singing voice. And I haven’t gotten anyone busted yet.

Let’s turn to the readings. I admit on the outset that this time I’ll be light on the exegesis, and hew instead more closely to my theme.

Exodus 32:7-11, 13-14

In this reading, God complains to Moses about his people. God wonders if they are still His people. They have set up a golden calf and called it God. God calls this “depravity,” when in fact it seems they just wanted a visual representation of God. God says: “Let me alone, then, that my wrath may blaze up against them to consume them. Then I will make of you a great nation.” When God says “let me alone,” he is assuming that Moses would challenge God on this. Moses’s role is to speak truth to power, whether he is speaking to his people or to God. After all, God is threatening genocide. But that’s all right, God says; I will wipe out all these people, but I will make of you a great nation. Moses might have thought: where have I heard this before? Didn’t God say the same thing to Adam and Eve, right before he banished them from the garden? Didn’t God say the same thing to Noah after he wiped out all the people in the world, except for Noah and his family? Didn’t God say the same thing to Abraham, right before he ordered Abraham to sacrifice is only son? And now he was saying it to Moses, after threatening to kill the people he had taken so much trouble to liberate from the Egyptians.

Moses dares to point all this out to God, and reminds God that God promised to make the descendants of Abraham, Isaac, and Israel “as numerous as the stars in the sky.” God is convinced by Moses. God “relented in the punishment he had threated to inflict on his people.” Older translations say that God “repented” from what he had planned. But it is borderline blasphemous and heretical to say that our perfect, omniscient and all-powerful God “repented,” that he turned away from doing evil (which some older translations also say: that God repented of doing evil). That is what seems to be suggested by those who chose the lectionary readings. All the other readings are about repentance. In this reading, God repents. But is it really heretical to suggest that God learns from his mistakes, that God grows, comes to self-knowledge and consciousness, in the ways that people do? If not, we are faced with the specter of another heresy, that of Marcionism.

According to the ancient Christian writer Marcion, Christianity reveals the true God, the God of love, forgiveness, and compassion; whereas, the God of the Hebrew Scriptures is a false god, a god of vengeance and hatred. This position has been declared heretical by the Church, and rightly so, because it denigrates Judaism and justifies anti-Semitism, anti-Jewish pogroms, and the Holocaust. But how then do we explain the God of much of the Hebrew Scriptures—who is a jealous god, who is sometimes seemingly genocidal and urges a genocidal mentality, ironically enough, upon the Jewish people—compared to the God that Jesus describes, who is a God of infinite love and compassion? And how do we explain a God who is, in the Hebrew Scriptures, a practitioner of conditional love, with the God of Jesus, who practices unconditional love?

One explanation is that God changes, that God experiences metanoia. Another explanation is that it is in fact the human understanding of God that changes, rather than God him/herself. The savage God who sometimes appears in the Hebrew scriptures is really the way God was perceived by a savage, or at least a primitive, people. By the time Jesus came along, these people were no longer savage or primitive; they had come to know God, through the experience of centuries, to be an infinitely compassionate being.

This suggests that the Hebrew and Christian scriptures are fictional in the sense that fiction is an art form by which we come to the truth by means of creative falsity. It is also an art form by which characters come to the truth by way of action in the world, by waywardness, followed by reflection upon action and waywardness. Thus individuals, peoples, and even gods change and become more highly evolved. This takes us a little bit off course, so I’ll leave it there.

Paul’s Letter to Timothy 1:12-17

According to Paul, Jesus came into the world to save sinners. “Of these I am the foremost,” Paul says.

Paul is proclaiming himself a prodigal son: once a just man, a progressive Pharisee, he has become a fanatical persecutor, a murderer, a mass murderer, a serial killer. In doing so, he “acted out of ignorance” in his “unbelief.” But his letter to Timothy suggests that Paul would not be who he was if he had not gone astray. “For that reason I was mercifully treated, so that in me, as the foremost, Christ Jesus might display all his patience as an example for those who come to believe in him.”

Paul does not dwell on his sinfulness but instead on how he has become reconciled. He admits to being an imperfect apostle, and that by way of his imperfection he has come to a more perfect understanding of a compassionate, loving God.

We might say the same thing about the Church. If one of the two inventors of the Church (with Peter) can be imperfect, so too can the Church. And just as Paul—and as God, in Exodus—can gain by going astray, off-path, so too can the Church learn from its mistakes. The current pope has a good grasp of this. He freely admits, and regularly apologizes for the transgressions of the Church. He has done much to heal the damage wrought by the priest sex abuse scandal. Lately, as another example, he has apologized for the persecution of gays and lesbians in the Church. The Church of Pope Francis is a prodigal church, returning to the values promulgated by its founder, such as mercy, compassion, and unconditional love.

Luke 15:1-32 (The Lost Sheep, Coin, Son)

In my discussion of the gospel reading today—which, along with the parable of the prodigal son, also includes the parables of the lost sheep and the lost coin—I’ll be drawing upon the work of Amy-Jill Levine. In her book The Short Stories of Jesus, she includes a whole chapter on the cluster of these three parables.

Levine, a Jewish scholar and professor of New Testament Studies at Vanderbilt University Divinity School, devotes most of her chapter to answering and arguing against anti-Semitic interpretations of these parables. For instance, some interpreters see the father in the parable of the prodigal son as a representation of God, a God who is loving, and compassionate, and thus radically different from the God of the Hebrew Scriptures. In other words, they suggest an interpretation that is Marcionistic. In fact, Levine points out, this compassionate father is not that different from Jewish fathers of Jesus’s day, and not that different from the loving God who appears in the Hebrew Scriptures, particularly in the prophets.

Levine also argues against the interpretation that sees the parables in today’s gospel reading as being about repentance. Regarding the parables of the lost sheep and the lost coin, she simply points out that sheep and coins can’t repent. Levine argues that these stories are more about reconciliation than repentance.

Before moving on to the parable of the Prodigal Son, let’s consider the parables of the lost sheep and the lost coin. Are there elements of prodigality in these two stories? I would say, with some back up from Levine, yes. The shepherd is prodigal—that is, he’s reckless and wasteful, in abandoning his ninety-nine sheep to find the one who was lost, and then throwing a party to celebrate finding the one sheep (Levine facetiously comments that she wouldn’t have been surprised if the shepherd had served mutton at the party!). The woman who loses the coin is reckless and wasteful in throwing a party to celebrate finding one coin. The suggestion here is that the party cost her much more than that one coin.

What this illustrates is what the father in the parable of the prodigal son represents—God’s reckless and wasteful dispensation of his/her resources. This is a wonderful definition of God’s grace! The point here is that what causes the celebration is not so much repentance (again, sheep and coins can’t repent) but the joy that results from reconciliation—from finding what was lost, as opposed to the conviction of sin, of guilt.

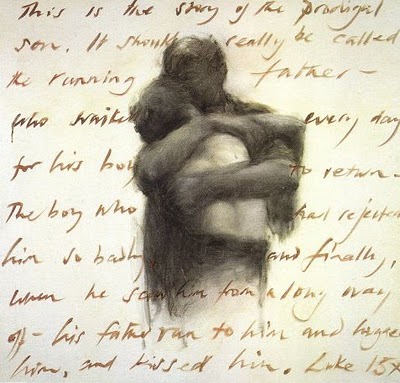

This is my reading, anyway, of the parable of the prodigal son. The first prodigal son is prodigal in both definitions I set out at the beginning. He is wasteful, and engages in acts of moral depravity. But he returns and experiences his father’s prodigality: the father gives his wayward son the best robe and kills for him the fatted calf. This prodigal son did not deserve it, but such was the unconditional love of his father. In the same way, humans don’t deserve God’s riches, God’s grace, but God recklessly disposes them upon us anyway.

So the father is prodigal in his reckless generosity. Which made me wonder: how did he come about this belief in unconditional love? How do any of us come to such a belief? Often it’s an experience of conditional love that goes badly. Perhaps there was a third son that we don’t hear about in the parable. Perhaps once upon a time this third son performed an act of generosity with his father’s property which angered the father (like what happened to St. Francis of Assisi and his father). This third son might then have gone off and not returned—perhaps he died in a faraway land, unreconciled with his father, leaving the father to lament his lack of generosity and understanding. Such an experience would explain the radical generosity, the unconditional love, of the father in the parable of the prodigal son.

And if we see the father in the parable as a stand-in for God, we might understand Jesus to be representing a God who has learned from his mistakes with the people of Israel, when they were in the desert and more particularly when they were a nation mimicking the empires that surrounded them, worshiping the idols of wealth and power.

What then of the second son? I mentioned that he is prodigal too. He is prodigal in the sense that he has gone astray upon the straight and narrow. He has fulfilled all the commandments, all the law, but lacks the insight and compassion that comes from going off the path, from wandering in the desert.

Our prodigal nation

I end with a reflection upon the terror attacks of 9/11/2001.

I will begin by saying that I’m becoming more and more convinced that those who claim 9/11 was an inside job are right. The arguments of people like David Ray Griffin and Jim Douglass (and our dear friends Kathy Boylan and John Schuchardt) are suggestive and persuasive. It seems impossible to believe that the clinical demolition of the World Trade buildings was done by way of flying planes into them and dousing them with airplane fuel (particularly when one of the fallen buildings was not hit by an airplane). The lack of photographic evidence of a plane crash at the Pentagon is also suspicious. Whether it was the Bush administration that dynamited those buildings, or knew about it and let it happen, the hawkish members of the Bush II cabal certainly used the destruction of the World Trade Center to further their nefarious ends.

But for me the greater crime was to take the country-wide commiseration and camaraderie that followed the killing of three thousand innocent people, and twist it into blood-thirsty revenge, leading the United States into two (at least) wars, and the murder of a hundred times as many innocent noncombatants in Afghanistan and the Middle East.

In the wake of 9/11, the United States has been prodigal in both senses of the definition I used at the outset. Many billions of dollars have been wasted on the destruction of two countries and the deaths of hundreds of thousands. Wasteful and wanton, to say the least. Profligate and morally depraved, for sure.

All that said, I find the “9/11 was an inside job” narrative to be extremely alienating and disempowering. It’s the depiction of a nation that is irredeemable; that is, in fact demonic. I prefer to see our nation as prodigal, rather than demonic. I hold out hope that we as a nation might find ways to use our wealth to aid the poorer nations of the world, rather than destroy them. That we might be recklessly generous with methods of education and enlightenment, modeling the values of nonviolence, of peace with justice, and true democracy.

If metanoia is possible for people, it must be possible for nations as well; it must be possible for worlds such as ours. America the prodigal must be able to step away from the brink, to return from the wilderness, having learned from our grievous mistakes. If not, we are all lost, trapped in a world that is one big prison, in a permanent desert of our own making.

I end this reflection with questions for our discussion. How might our prodigal nation return to the community of nations (rejecting the superpower label, or any notion of empire) and to the values that inspired the American revolution, and inspire the world still. How might we learn from our mistakes since 9/11 and be better for it?

How might our prodigal Church return to the values preached and embodied by Jesus?

How have we experienced our own prodigality? According to which definition (positive and negative sense of prodigality)?